More than 90 percent of our political leadership positions are held by men. If this trend continues, future generations will grow up with male role models as leaders of their countries. Scientific studies have started to explore why this is the case, why it is that more men are in political leadership positions than possible female counterparts, and what, if anything, can be done to recalibrate and strike a balance within our systems. These findings suggest that the answer, in part, lies in the choices we make in politics.

Last week, while blogging for Faces of Science, a Dutch initiative where young scholars share stories about life in academia, I discussed the topic of female leadership. Although this is not the key focus of my research, I do teach on the subject and keep a database on the number of female leaders in EU institutions (spoiler alert: very few).

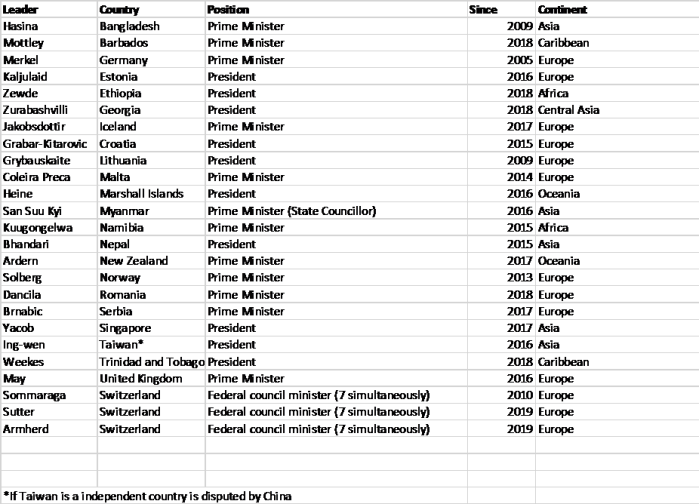

From the heads of state or government (roughly 300), only 25 are female. Within the EU, we have six heads of state and two prime ministers (soon to be one with March 29 approaching). Outside the EU, there are five more heads of state or government on the European continent, two in the Caribbean, two in Africa, five in Asia, two in Oceania, one in Central-Asia and none in South- or North America.

Figure 1: female leaders on International Women’s Day 2019. Source: own data.

In short: men still dominate the world stage of leadership. How come? Science is here to provide you with answers. I walk through some of the latest studies to show where, according to science, we could pay attention to to increase the number of female leaders worldwide. I’ll leave it to politics to decide

Point 1: stereotypes distort our image of a ‘good’ leader

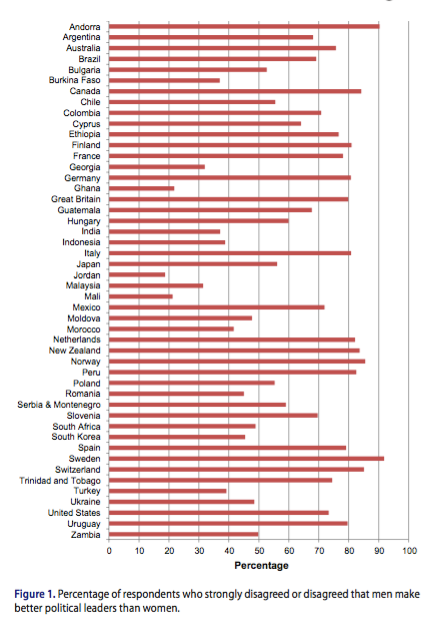

When asked, people disagree or strongly disagree with the statement that men are better leaders than women (see figure 2, results from the World Value Survey (n=28)).

Source: Allen and Cutts, 2018: 152-153

However, our implicit assumptions about men and women do paint a different picture than when we’re asked to reflect upon our opinions. Implicit assumption tests[1], where we see photos of both men and women and have to link them to words relating to leadership or followership as fast as possible, show how we, in general, find it easier to link male photos to leadership words than female photos. When asked, the results show marginal differences, but our implicit assumptions do impact how we respond in reality. This is what we can refer to as ‘gender bias’. This gender bias basically shows that we have different expectations regarding men and women in leadership positions, and not that women truly have distinct leadership qualities than man.

These gender stereotypes create a ‘no-win’ situation for female leaders. This is referred to as the ‘double bind’. This means that there’s a contradiction between how we perceive women in political positions and what we expect from them as women. Thinking in terms of stereotypes as ‘men take charge and women are more caring’, the following happens. When women take charge, they are seen as competent – but not appreciated as women.

Textbox: one very recent example is a critique on Euro-parliamentarian Judith Sargentini, who wrote a critical report on the state of democracy in Hungary. The tweet below, sent into the world after Sargentini performed on Dutch television, translates to: “My wife was inspired by Sargentini during the talk show tonight and has decided on her carnival costume”.

Alternatively, when women take up ‘caring roles’ they are not taken seriously as leaders. Think about the many self-help books in which women are told to not behave as women if they want to be effective leaders. Books as ‘Nice girls don’t get the corner office’ or ‘Lean in’ are perfect examples of this.

If we want to do something about this, we can. There’s a role for us, for the media and for politics to work towards ‘bias consciousness’. A recent article by Loes Aaldering and Daphne van der Pas (2018) shows results from a quantitative content analysis of Dutch newspaper articles. Here the authors demonstrate that Dutch newspapers attribute more leadership qualities to male party leaders than to female party leaders. Some kind of gender-check in newsrooms may be a first step towards a more gender-neutral reporting culture.

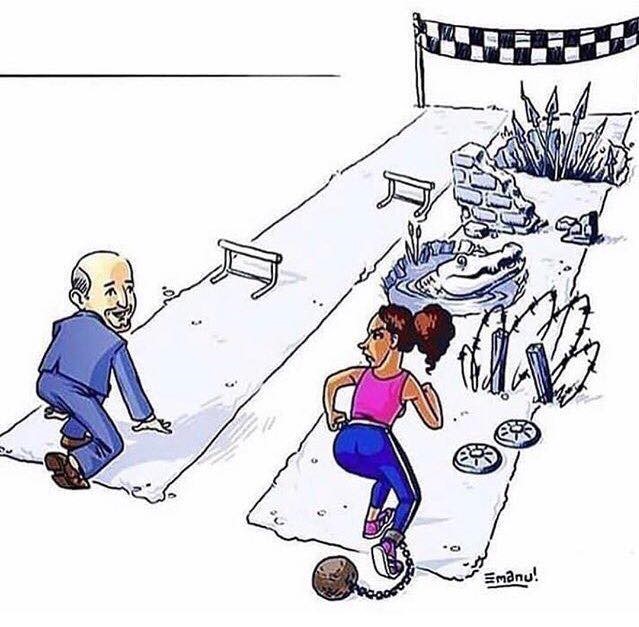

Point 2: pathways to power are more difficult for women than for men.

Geerten Waling, a Dutch historian, said the following in a radio interview on Dutch radio this year: “…women just have to bang through the glass ceiling with an iron fist”. Obviously, women try, but men and women keep systems in place that make it difficult for women to, in the words of Waling, bang through the ceiling. Institutional sexism. This means that we don’t think that women are worse than men, but that inequality can be traced back to the institutional structures that we’re part of), is one of the reasons why the whole ‘banging through glass ceilings’ is extremely difficult. One example is the appointment of ‘crown princes’, as Jean Claude Juncker did with Martin Selmayr as top civil service executive in the European Commission. Institutional sexism makes the pathways to power more complicated for women than for men.

Research by Farida Jalalzai (2018) demonstrates that of the female leaders we currently have, few have taken their seat by popular vote. In addition, most female leaders govern in shared power systems (semi-presidential) and as such have less power resources than their male counterparts.

Other research by Muller-Rommel and Verseci (2017) shows that in the EU, female prime ministers had a far more complicated pathway to power than their male counterparts. Female prime ministers in general need more professional experience before being able to assume office. Furthermore, the study’s results show that female prime ministers mostly come from centre-right parties.

Political-institutional conditions such as primaries or appointment procedures can further hinder the rise of female leaders, creating formidable barriers and multiple constraints from an early point in their career. These are not just once-off barriers. They build up and make it more difficult to women to break through. More frequent pathways to power for women are either familial ties (such as Hillary Clinton), or ‘chance openings’ (such as Margaret Thatcher, who seemed to be promoted due to weaknesses of others, not her own strengths).

In short: according to science, we should think about ways to reduce institutional sexism to level the playing field and give women equal chances as men in their pathways to power. This may entail critically examining selection or appointment procedures (e.g. when choosing a new party leader).

Point 3: quotas work but they’re considered ‘principally undesirable’.

A third point that we see in discussions about female leadership is that ‘time will tell’. Just stick it out and things will change. After all, the numbers seem to have increased in recent years, right? Recent studies show that this argument doesn’t stand. Without incentives or quota measures, it takes a very long time to achieve any kind of balance. If we want future generations to grow up in a world where women are world leaders as well, we don’t have that kind of time. An interesting study by Peter Allen and David Cutts (2018) shows that the much-disputed incentives of quota systems increases political support for women. So, not only do we have more women through quotas (duh!), but these women actually gain increased support from their constituents. The authors refer to this as the ‘vote of confidence’ effect. Quotas remain a highly disputed instrument though (the poll I held last week on Instagram showed a 47 against -53 in favor result). Most used argument: who wants to be the ‘token’ woman? However, if we trust science, quotas should be taken seriously as they change the narrative of ‘token’ women into credible partners in politics.

So, what can we do in the world of politics now and in the future:

- Combat institutional sexism to equalize the pathways to power for men and women

- Increase our consciousness of stereotypes of women in politics.

- Use quotas to increase the visibility of women in politics. This has the enhanced benefit of increasing support for women in politics.

Further Reading

Aaldering, L., & Van Der Pas, D. J. (2018). Political leadership in the media: Gender bias in leader stereotypes during campaign and routine times. British Journal of Political Science, 1-21. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-political-science/article/political-leadership-in-the-media-gender-bias-in-leader-stereotypes-during-campaign-and-routine-times/B197672D2B8A6BCB0A65920396151699

Alexander, A. C., Bolzendahl, C., & Jalalzai, F. (Eds.). (2017). Measuring Women’s Political Empowerment across the Globe: Strategies, Challenges and Future Research. Springer.

Müller-Rommel, F., & Vercesi, M. (2017). Prime ministerial careers in the European Union: does gender make a difference?. European Politics and Society, 18(2), 245-262.

** This blog has appeared in Dutch on my Faces of Science webpage. Special thanks to Jo Luetjens for proofreading the translated version.

[1] Want to try? https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/user/agg/blindspot/indexgc.htm